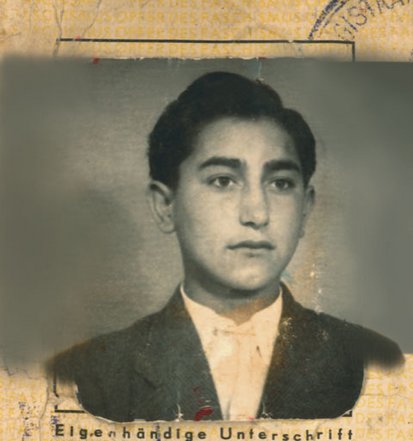

Otto Rosenberg (1927-2001)

The German Sinto Otto Rosenberg was born in 1927 in East Prussia, in what is now Kaliningrad. He grew up with his grandmother in Berlin. In his autobiography, Das Brennglas (“The Magnifying Glass”) Rosenberg recalls a childhood marked by family cohesion and social security. For Otto Rosenberg, it was perfectly natural for Sinti to be integrated into Berlin city life. Although he experienced racism even while he was at school, the radical break came for him under Nazi rule.

Racially motivated forcible internment

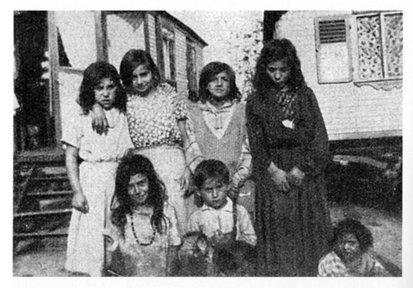

When Otto Rosenberg was nine years old, the Nazis arrested him and his family and sent them to an internment camp in Marzahn, which they euphemistically called a “rest area”. The forced internment of Berlin’s Sinti and Roma minority had been planned by the Nazi authorities for some time. The Olympic Games in the summer of 1936 provided them with a pretext for interning Sinti, Roma and others persecuted as “gypsies” in a central camp on the outskirts of Berlin. Such internments took place in many German cities.

The Marzahn camp had no electricity or water supply. Otto Rosenberg recalls in his memoirs that coal and food had to be fetched on foot from the village of Marzahn. Children and young people could no longer attend regular schools. Everyday life in the camp was marked by external control and punishment by the guards.

The Sinti and Roma interned in the Marzahn camp were registered by “racial scientists”. They were defined and classified according to racist and eugenicist criteria in pseudo-scientific reports by the Rassenhygienische Forschungsstelle (RHF), an institute of the Reich Health Office. In line with Nazi ideology, the RHF’s task was to “explain” in racial terms the alleged criminality of which Sinti and Roma were stereotypically accused. The RHF, its head, Robert Ritter, and his deputy, Eva Justin, laid the foundations for the persecution, forced sterilisation and murder of Sinti and Roma. In his memoirs, Otto Rosenberg reports that Ritter and Justin also visited the Marzahn internment camp. They used force and violence to examine and interrogate the people interned there, deeply violating their privacy.

As a child in forced labour

At the age of thirteen, Otto Rosenberg was forced to leave the school in the camp and work as a forced labourer at the Danneberg & Quandt (DAQUA) armaments factory. Everyday working life there was heavily influenced by the racist hierarchy of Nazi ideology. Otto Rosenberg was paid less than his colleagues and was eventually even excluded from the communal meals.

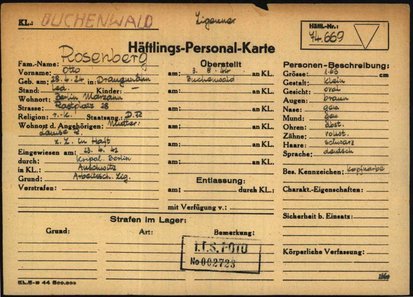

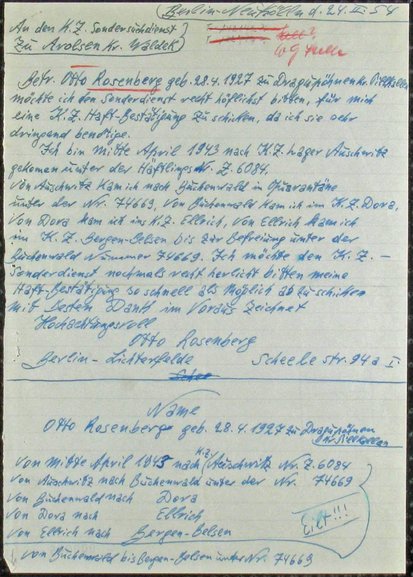

Deportation to Auschwitz and Buchenwald

When he was denounced by his colleagues for alleged sabotage, the police arrested him. Otto Rosenberg had to spend four months in solitary confinement in Moabit prison. In April 1943, shortly before his fifteenth birthday, he was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration and death camp, where he suffered from cold, starvation and illness. On 16 May 1944, Otto Rosenberg took part in the collective resistance in Birkenau, which for a short time prevented the planned murder of all remaining Roma and Sinti prisoners.

In August 1944, Otto Rosenberg was transported to Buchenwald concentration camp, where he was forced to work in a quarry. The remaining 4,200 to 4,300 Sinti and Roma of the Birkenau death camp were murdered in the gas chambers during the night of 2 to 3 August.

Via the Mittelbau-Dora camp Otto Rosenberg then came to the Juliushütte satellite camp, where the SS used prisoners for underground tunnel construction in the Kohnstein hill for the production of what was referred to by Nazi propaganda as a “superweapon”, the V2 rocket. The camp was cleared in early April 1945.

Survival

The last transportation to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp was marked by the starvation, illness and disorientation of the prisoners. The British Army liberated Bergen-Belsen in April 1945. Otto Rosenberg was the only one of his eleven siblings to survive. After spending several weeks in a hospital in Celle, he made his way back to Berlin.

The long struggle for recognition

Otto Rosenberg had to go to the Berlin Regional Court to obtain a compensation payment. With the continued discrimination against Sinti and Roma in post-war Germany, he was denied societal recognition for a long time.

Following his marriage in 1953, Otto Rosenberg and his wife had seven children. He worked as a musician and antiques dealer.

Since the 1980s, Otto Rosenberg was politically active, fighting for social equality for Sinti and Roma. He was a co-founder and for many years chairman of the Berlin-Brandenburg branch of the German Sinti and Roma Association.

Otto Rosenberg died on 4 July 2001 from the long-term effects of his imprisonment in the concentration camps.