Essay

Forced Labour in German Colonies

by Jonas Kreienbaum

The European colonial powers usually justified the acquisition of colonies in the 19th and early 20th centuries on the grounds of a “civilizing mission”. This was true of the German Empire, which acquired colonies in Africa, China, and the Pacific from 1884 onwards, and older colonial powers such as Britain, France, and Portugal. This “civilizing mission” included putting an end to the slave trade and slavery, in which the colonial powers themselves had usually been actively involved for centuries. Without recourse to slave labour, however, the colonisers found it extremely difficult to persuade the colonised peoples to work on European plantations, farms, in mines or on railways. The economic goals of colonialism, such as opening up new markets for their exports and obtaining raw materials, could hardly be achieved in this way. The so-called “labour question”, therefore, was one of the dominant themes of all colonial policies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. All European colonial powers experimented with various forms of coercion to mobilise local labour.

The slow death of slavery

While colonial governments were passing laws against the slave trade, they took no consistent action at all, despite all their civilising rhetoric against slavery practices. This was because, especially in the phase when they were establishing colonial rule, they depended upon the cooperation of African elites who were themselves, in some regions at least, among the biggest enslavers. Colonial officials were also afraid that a quick abolition of slavery would bring about a massive economic collapse. This is why in about 1900, fifteen years after the beginning of German rule, there were still around 400,000 enslaved people in the possession of African and Arab elites in “German East Africa”, a territory covering present-day Tanzania, Burundi and Rwanda. There were still 165,000 enslaved people even shortly before the outbreak of the First World War. Slavery did indeed die a very “slow death”, as historians Paul Lovejoy and Jan Hogendorn have put it.

Tax labour and passport decrees

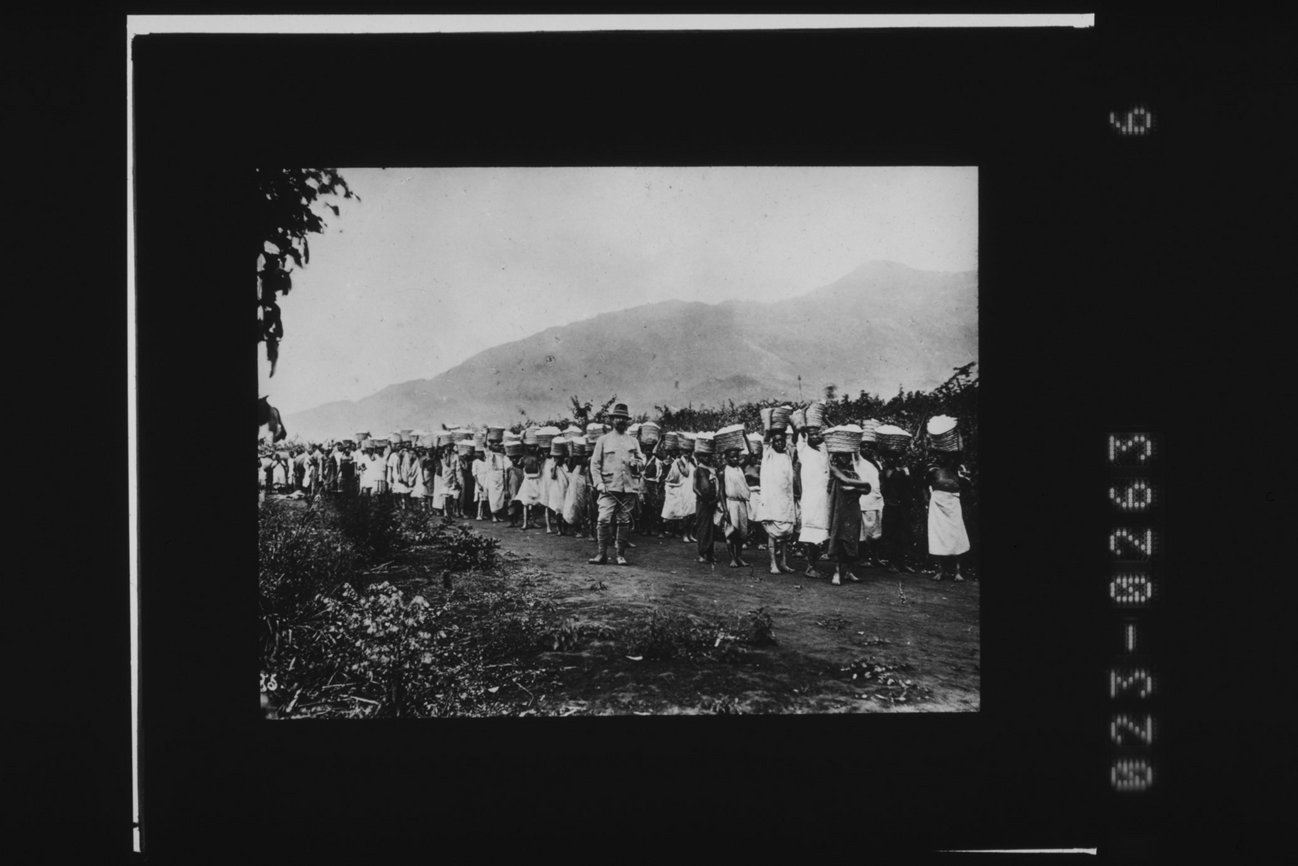

Another strategy to deal with the “labour problem” was the introduction of house and poll taxes and, in some colonies, the enactment of passport regulations and laws against “vagrancy”. In Togo, a German colony at the time, the tax could simply not be paid due to the lack of a cash economy and had to be paid by the male population as workdays. In reality, this “tax labour” was a form of forced labour, ordered largely arbitrarily by the district heads, and without which the construction of roads, administrative buildings or telegraph lines would have been unthinkable. Not least because of the arbitrariness and brutal violence that accompanied this form of forced labour, it provoked resistance from the colonised population. In most cases, they evaded the demands by emigrating. In East Africa, the introduction of a poll tax in 1905, which included forced labour in German cotton fields, was one of the main reasons for the outbreak of the Maji Maji Rebellion, in which the local population fought against the German colonial power.

Indentured labour

Another approach was the recruitment of African and Asian indentured labourers. The latter, often referred to as “coolies” at the time, were employed on a large scale on the North and South American plantations following the abolition of slavery in the Americas in the course of the 19th century. Recruited on a temporary basis but often under duress, the conditions under which these migrant workers were employed differed only gradually from those of earlier enslaved labourers. The German colonial administration sent some Chinese indentured labourers to Africa, but mainly to the Pacific colonies. In Samoa, where, unlike other German colonies, the indigenous population was not subject to forced labour, there were almost 4,000 Chinese indentured labourers by 1913. They worked mainly on coconut and cocoa plantations but successfully lobbied the Chinese state to take action against poor working conditions.

Camps, forced labour, and “education through work”

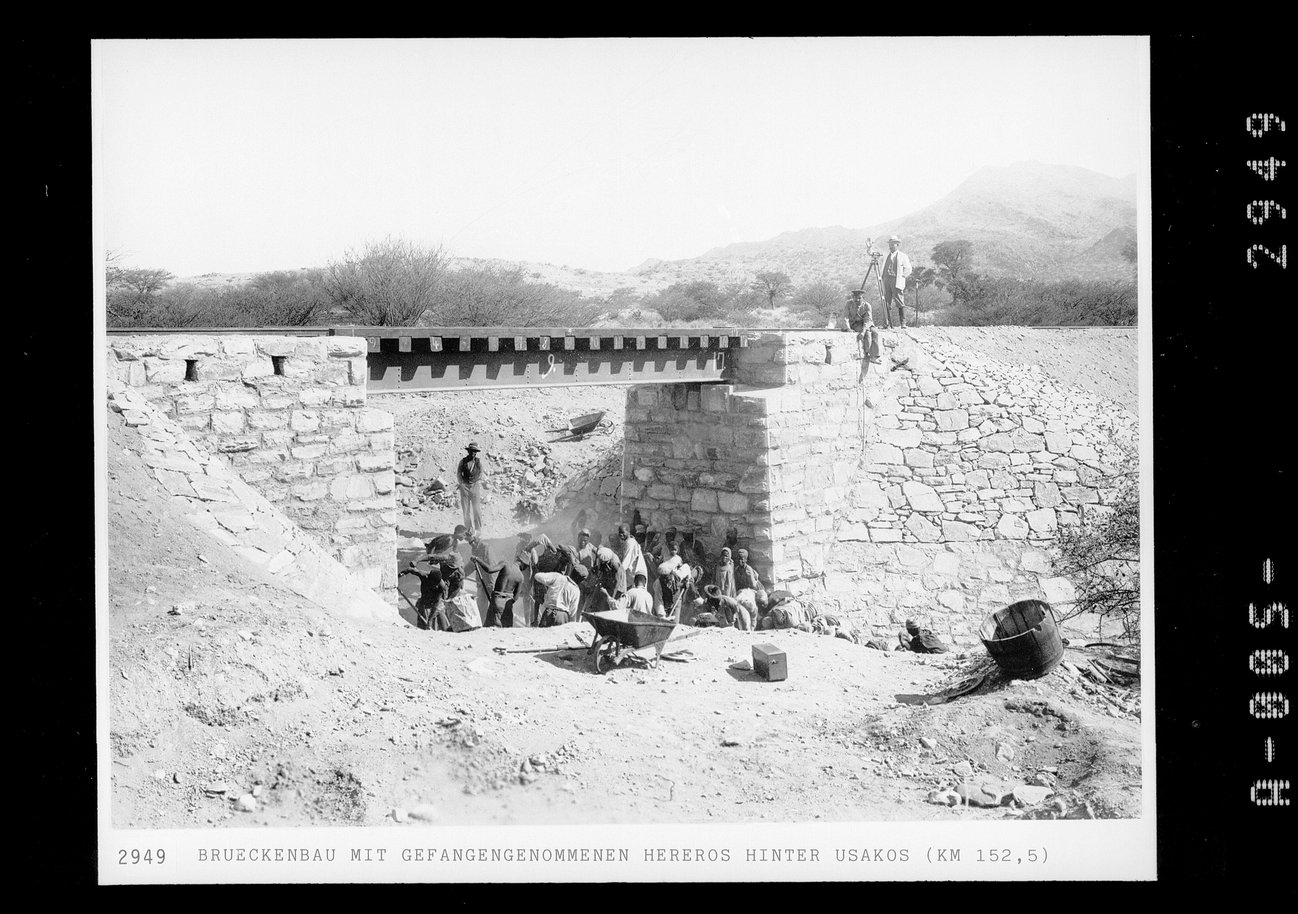

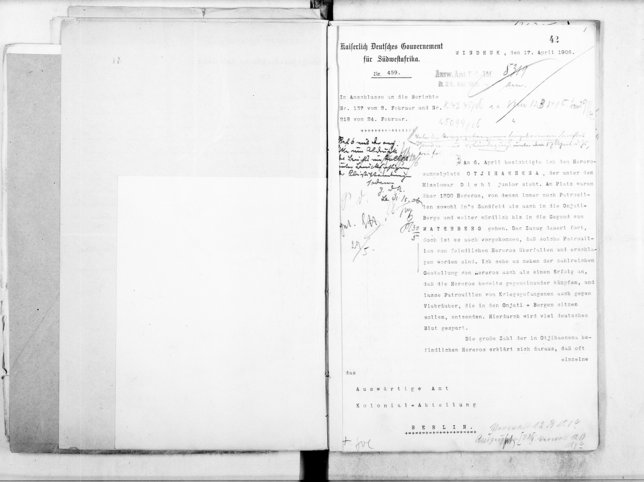

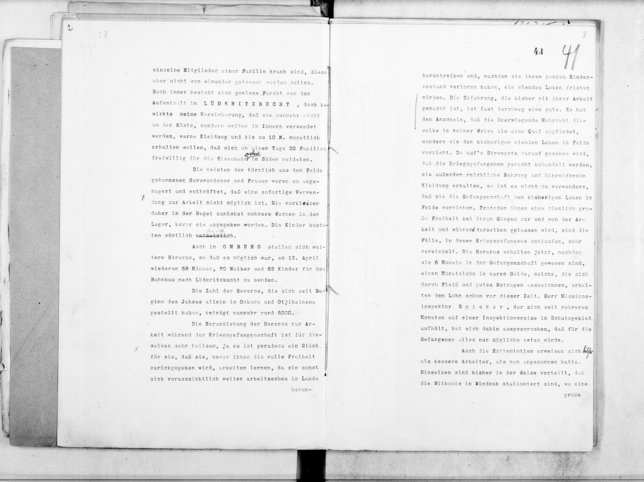

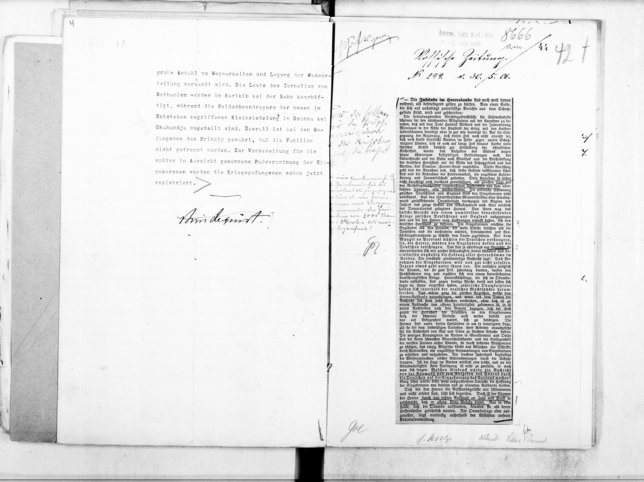

In the course of the genocidal war against the Herero and Nama (1904-1908), the Germans created the most brutal system of forced labour in the colony of “German South West Africa”, an area corresponding to modern-day Namibia. In early 1905, the Schutztruppe, as the German colonial military was known, set up a series of concentration camps in which they systematically forced some 25,000 prisoners to work. Similar to the later Nazi camps, the colonial state introduced a system of renting out prisoners. Captured OvaHerero and Nama were assigned to companies and settlers for forced labour in return for a rental fee, which had to be paid to the district office. As the overseers often used violence to force children and the sick to work, the mortality rate among forced labourers was extremely high.

The conditions under which the southern railway line was built from Lüderitz Bay to the interior were particularly horrific. At times, more than 10% of the 1,400 or so POWs assigned to the work died in a month. Yet despite this horrific violence, the Germans justified the forced labour as “education through work”, which they claimed was ultimately in the interests of the colonised people themselves. Governor Friedrich von Lindequist even said it was “an absolute blessing for them [the Herero] that they learn to work before full freedom is returned to them, as otherwise they would probably just hang around lazily in the country and ... endure a miserable existence”.

This kind of argument is emblematic of the racist colonialist logic used by the colonial powers to justify the exploitation of people in the colonies based on their supposed lack of work ethic.

Further Reading:

Eckert, Andreas: Der langsame Tod der Sklaverei. Unfreie Arbeit und Kolonialismus in Afrika im späten 19. und im 20. Jahrhundert, in: Elisabeth Hermann-Otto (Hg.): Sklaverei und Zwangsarbeit zwischen Akzeptanz und Widerstand, Hildesheim/Zürich/New York 2011, S. 309-322.

Habermas, Rebekka: Skandal in Togo. Ein Kapitel deutscher Kolonialherrschaft, Frankfurt a.M. 2016.

Haschemi, Minu: Koloniale Arbeit: Rassismus, Migration und Herrschaft in Tansania (1885-1914), Frankfurt/New York 2019.

Kreienbaum, Jonas: "Ein trauriges Fiasko". Koloniale Konzentrationslager im südlichen Afrika, 1900-1908, Hamburg 2015.