Marie R. (1919-unknown)

Marie R. was born in 1919 near Oschersleben in the Magdeburg Börde, the daughter of a working-class family. In 1936, at the age of 17, she left home for unknown reasons. A short while later, she was picked up by the police and sent to the St. Michael asylum in Niederschönhausen near Berlin.

In the same year, Marie was involuntarily sterilised under a court order. This forced sterilisation followed her psychiatric diagnoses of “feeble-mindedness”, “psychopathy”, “sexual instability” and “kleptomania”. Such diagnoses were commonly used in Nazi medicine and psychiatry to categorise undesirable behaviour as abnormal or pathological. We do not know what Marie made of these diagnoses, or how she saw herself.

How the Nazi regime dealt with non-conforming behaviour

The fact that Marie R. could be forcibly sterilised was due to the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring (Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses), which had come into force in 1934. With this law, and later with the Nuremberg Race Laws of 1935, the Nazis claimed total access to the bodies of people they considered racially, socially, and politically “inferior”.

This total power of disposal ranged from involuntary incarceration in state institutions to forced sterilisation and murder, euphemistically called “euthanasia”. This policy was pursued as part of the Nazis’ eugenicist project to create a supposed racially pure “body of the people” by preventing people who were considered inferior for various reasons (including mentally ill and disabled people) from having children and passing on their “hereditary material”.

The same was true of non-conforming behaviour, idleness and non-work. The Nazis regarded both as “biologically harmful” to the “body of the people” and criminalised them as antisocial. This essentially meant that the Nazis did not see crime and non-conforming behaviour as a social problem, but as a biological and genetic problem that could be “solved”. Only a small group of “career criminals” and “antisocial elements” were seen as genetically predisposed and responsible for crime. By systematically excluding and eventually killing them, the Nazis sought to eradicate criminality as a social phenomenon.

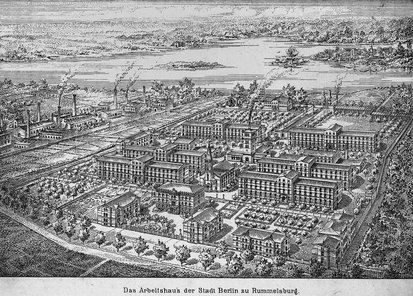

As a forced labourer in a workhouse

Marie was placed in custody shortly after her forced sterilisation and sent to another asylum. The Nazis probably regarded her as antisocial and – for various reasons including her psychiatric diagnoses and the perception of her sexuality – “inferior”. Her family were probably unable to pay for her stay in the asylum: Her father applied for her to be sent to a workhouse. Marie was placed in the Municipal Work and Detention House in Berlin-Lichtenberg, also known as the Rummelsburg Workhouse. Under the Nazi regime, the Rummelsburg Workhouse was a centre for the incarceration and forced labour of people stigmatised as antisocial. The internees were forced to work in labour detachments in the city, including in municipal facilities such as cemeteries, forests and parks, as well as in industrial companies and in the city’s basic utilities.

Marie was persecuted by the Nazis because she lived on the margins of society, because she was considered mentally ill, because she was poor, and ultimately because she did not fit into the Nazis’ totalitarian view of human life. Seen in this light, her persecution was ideologically part of the persecution of people whom the Nazis vaguely classified as antisocial.

Buried stories

When she was 21, Marie managed to escape from a labour detachment outside the workhouse, as the Rummelsburg administration reported on 14 May 1942. The story of Marie R. beyond this has been lost – we do not know anything about what happened to her.

The traces Marie R. left behind are only fragments of a whole and largely unknown life. Not even a photograph of her has survived. In the post-war period, only very few people were at all interested in the people persecuted by the Nazis on social-eugenicist grounds. Hardly anybody who had been defamed by the Nazis as antisocial or “alien to the community” was able to tell their story, including Marie R. What little information we have about her lives comes from the surviving documents of the perpetrators. The persecution of the socially marginalised also meant that their life stories were forgotten, distorted and ultimately told by others.