Forced Labour in the Course of the War

The system of Nazi forced labour was expanded as the Second World War progressed. Once the Wehrmacht had conquered a country, the local population was forced to work. According to the Nazis’ racist ideology, the people of the conquered countries were spoils of war. However, the deployment of forced labour did not follow a pre-established plan but was constantly adapted to meet the growing need for labour as the war went on.

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

Even before the start of the war, when the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia – the Czech part of Czechoslovakia occupied by the Germans – was formed, the local population were conscripted as forced labourers. Some were sent on three-month training courses in large armaments companies such as Siemens or Telefunken and then deployed in German subsidiary plants in the Protectorate. As the war wore on, the Nazi administration made increasing efforts to adapt the system of forced labour to new economic needs. From 1942 onwards, entire cohorts of Czechs were conscripted to work in the German Reich. This meant that all the men born in a given year had to work as forced labourers in Germany. Later, people were also rounded up in street raids for deportation.

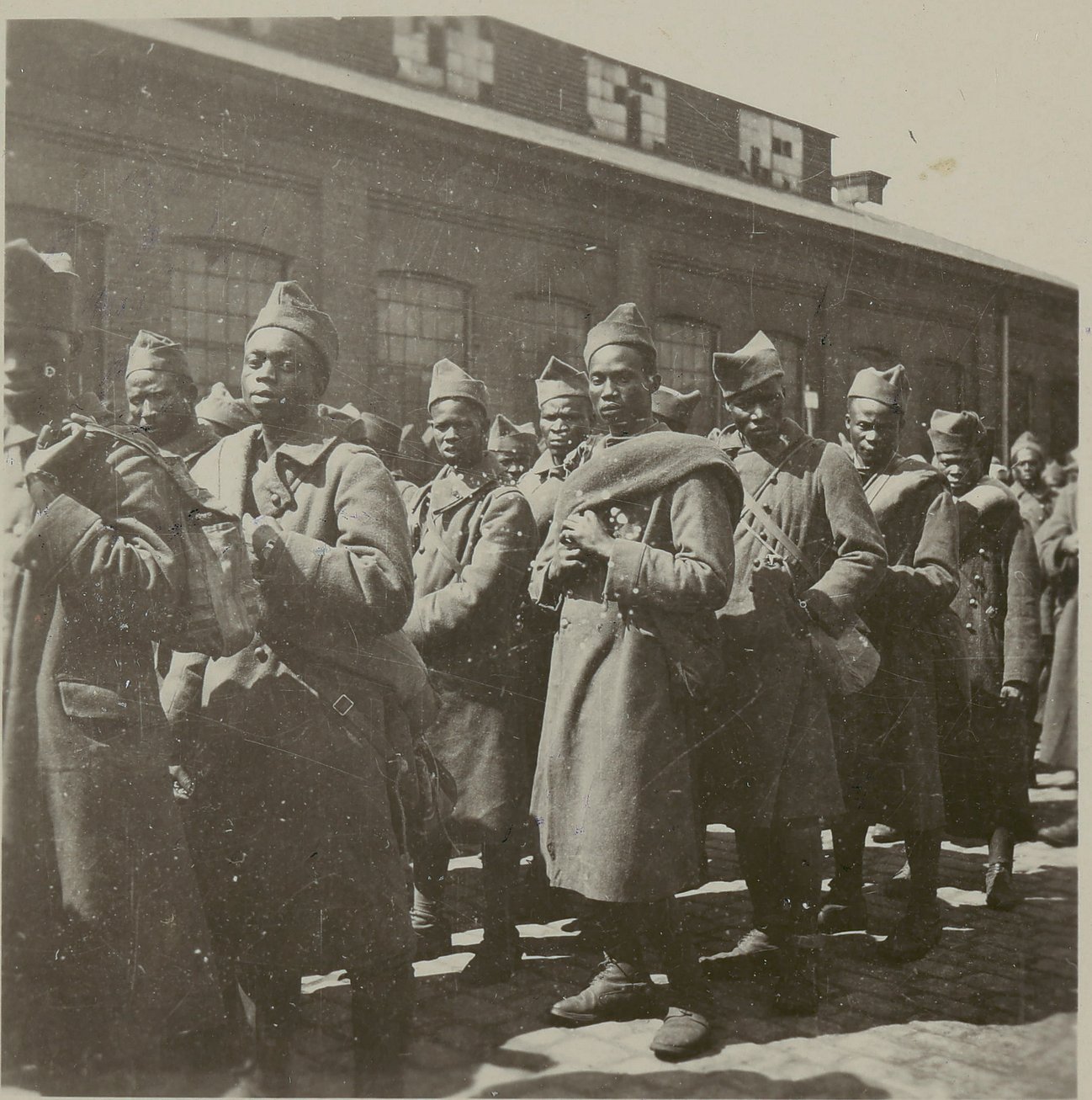

Prisoners of war as the first group

In September 1939, the Wehrmacht invaded Poland. This was the beginning of the Second World War. 600,000 Polish prisoners of war were subsequently deported to Germany where they were used as forced labourers in the agricultural sector. Many Polish soldiers were stripped of their POW status and assigned to so-called civilian forced labour. In this way, the Nazis deprived prisoners of war of their rights and could harshen their working conditions at will. At the same time, Polish civilians also were deported for forced labour.

In June 1940, the German Reich defeated France and the Benelux countries. Around 1.6 million prisoners of war were subsequently taken to Germany to do forced labour.

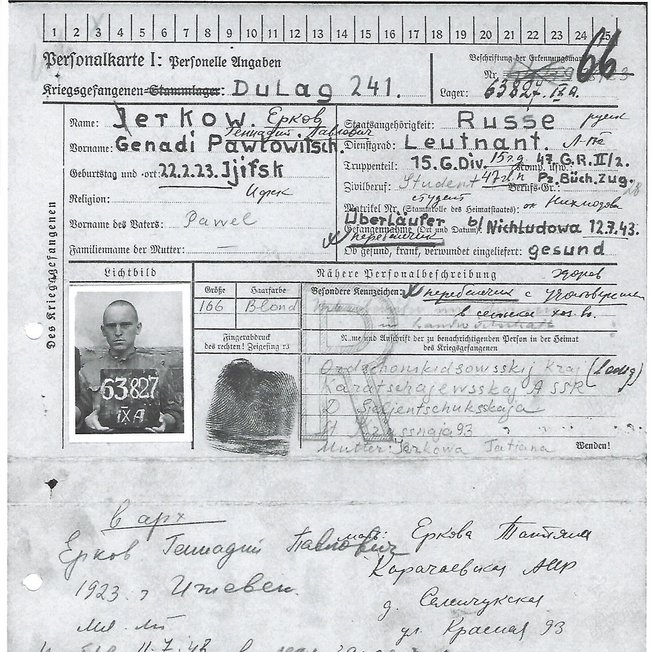

Invasion of the Soviet Union

The start of the war against the Soviet Union in June 1941 was a decisive turning point in the expansion of the system of Nazi forced labour. The war did not end in the expected quick victory but required the conscription of millions of able-bodied German men into the armed forces, the Wehrmacht, over a period of years. This meant that the German economy desperately needed workers. People from Eastern Europe were originally not supposed to be sent to the German Reich, so as to prevent them from coming into contact with Germans. This was supposed to maintain the purity of the German Volksgemeinschaft (“community of the People”), a product of Nazi fantasy. The Nazi regime also feared possible uprisings and a communist infiltration of society. But the Nazis were not able to maintain this policy of strict segregation because of the protracted war and the resulting shortage of labour in Germany. From the autumn of 1941, prisoners of war from the Soviet Union were also used as forced labourers. In addition, entire communities – men, women, adolescents and children – were deported to Germany and forced to work.

The pressure on the populations of the other occupied territories was also increased. Compulsory labour service in the German Reich was introduced for adults from Belgium and France from 1942. In the Netherlands, entire cohorts were deported to Germany for forced labour from 1943.

In September 1943, Italy withdrew from its alliance with Germany. The Wehrmacht then captured Italian soldiers and officers. Around 650,000 Italians were deported to the German Reich and the occupied territories. In 1944, their status was changed to “military internees”, which meant that they could be used for forced labour in the armaments industry, regardless of international law.

The number of forced labourers deported increased massively throughout the war. In 1939, there were around 300,000 foreign workers in Germany, but by 1944, this figure had risen to around 7 million.

A total of 13 million people were forced to work in the territory of the German Reich. The largest group of civilian forced labourers were the around 2.8 million people from the parts of the occupied Soviet Union. Most of them came from Ukraine, but there was also a large number from Belarus and Russia. Approximately 1.6 million forced labourers came from Poland. While many of those deported from Eastern Europe were women and adolescents, the groups of Western European forced labourers were predominantly men. An estimated 1 million people from France, 880,000 from Italy, 475,000 from the Netherlands, 325,000 from Belgium, 355,000 from Czechoslovakia, 100,000 from Serbia and many more from other countries were forced to work in Germany.

Germany was the organisational hub for the forced migration of millions of people. Soviet prisoners of war, for instance, were forced to dig ditches in Norway, and concentration camp prisoners from Auschwitz were taken to the German Reich when German production facilities were moved in 1944 and 1945.

Further Reading:

Mark Spoerer, Zwangsarbeit unter dem Hakenkreuz. Ausländische Zivilarbeiter, Kriegsgefangene und Häftlinge im Deutschen Reich und im besetzten Europa 1939-1945, Stuttgart/München 2001.

Ulrich Herbert, Fremdarbeiter. Politik und Praxis des "Ausländer-Einsatzes" in der Kriegswirtschaft des Dritten Reiches, Berlin/Bonn 1999.