Flight and Resistance

Flight

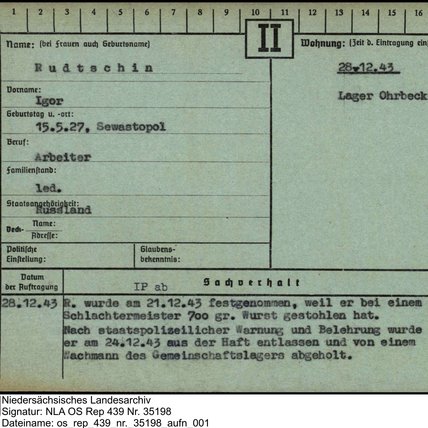

Forced labourers were not allowed to leave their jobs of their own accord, nor were they allowed to return home. Brief holidays were the only way to legally leave Germany for a limited period. Polish people, however, were only granted holiday leave in exceptional cases, and people from the Soviet Union were generally not allowed to leave the country. Forced labourers from abroad, then, were denied the right to return home to varying degrees. However, if there were special reasons, such as an injury, illness or pregnancy, they could travel home regardless of their leave. Forced labourers tried to use this to escape the demeaning conditions of forced labour and return home. People injured themselves, tried to get pregnant or went into hiding as soon as they were on home leave. The German administration increasingly recognised this as a strategy and decided that even injured, sick and pregnant forced labourers had to remain at their German place of work.

If they attempted to escape, they faced harsh penalties such as imprisonment in a work education camp or concentration camp. Nevertheless, many took the risk: according to estimates by the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), around 45,000 foreign forced labourers fled their workplaces every month in 1943.

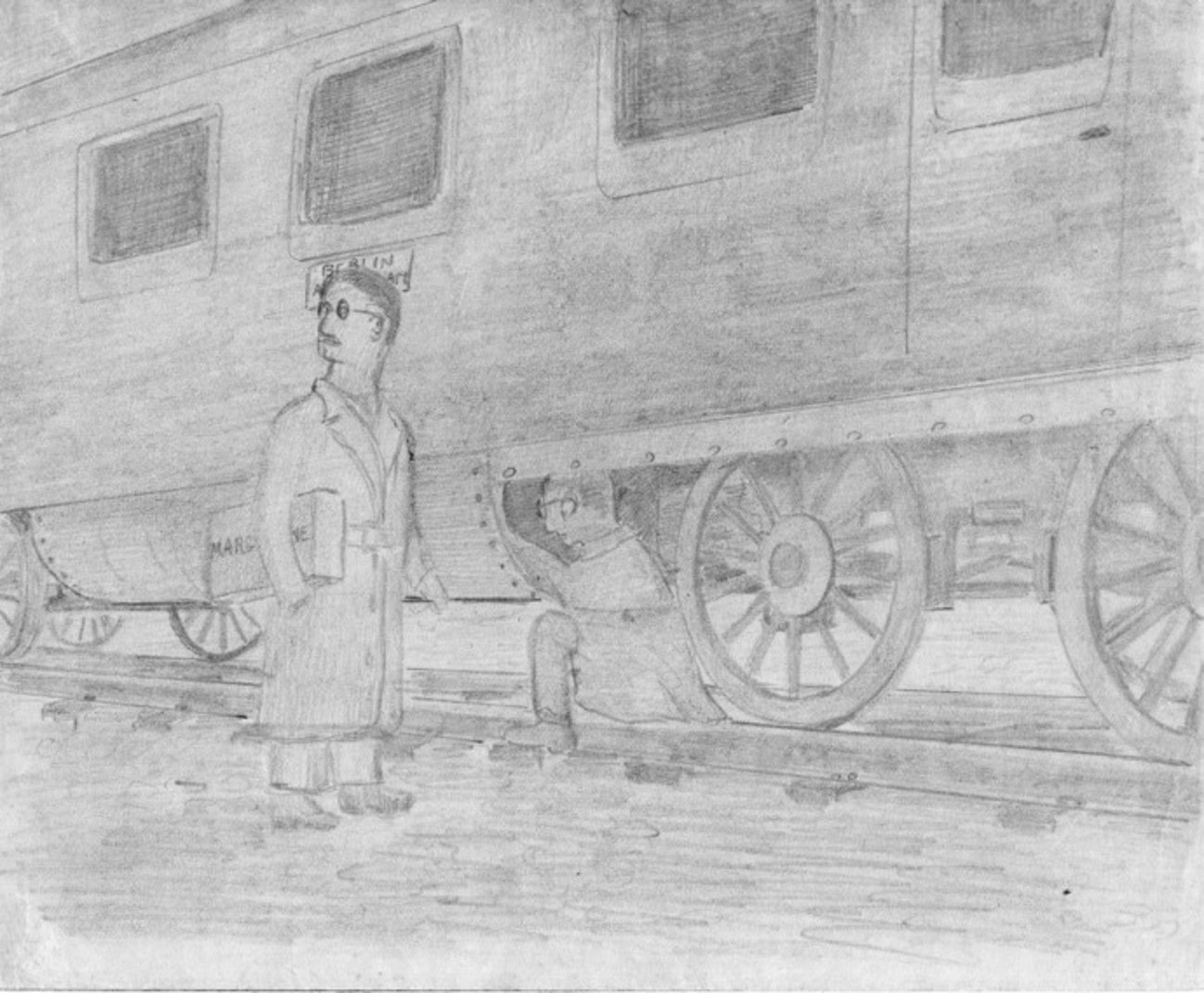

Coenraad Liebrecht Temminck-Groll was a forced labourer in Berlin. Like all forced labourers from the Netherlands, he could move around the city relatively freely outside of work, which he used to escape. With the aid of smugglers, he hid under a train that took him directly from Berlin to his home city of Amsterdam, where he successfully went into hiding until the end of the war.

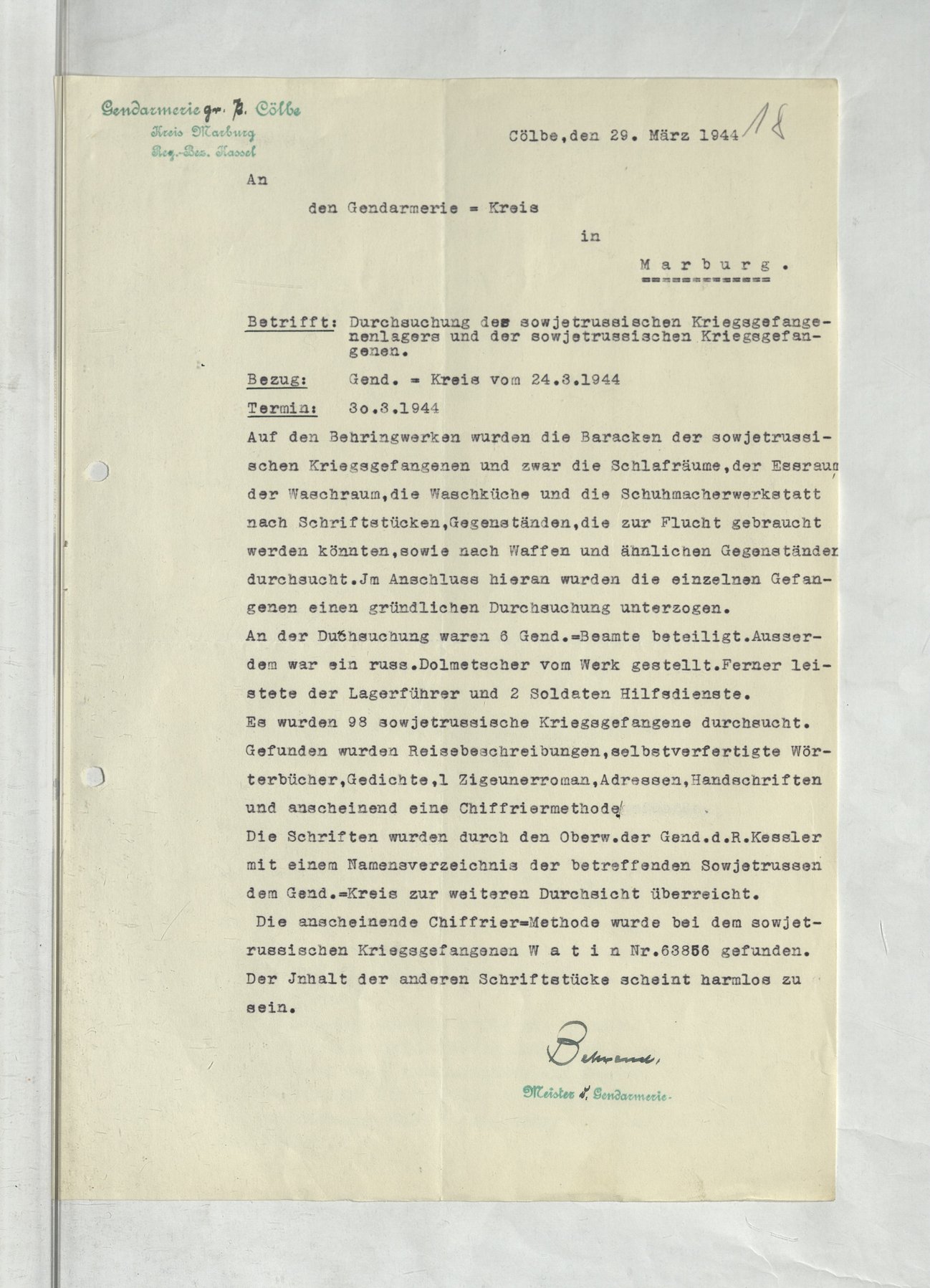

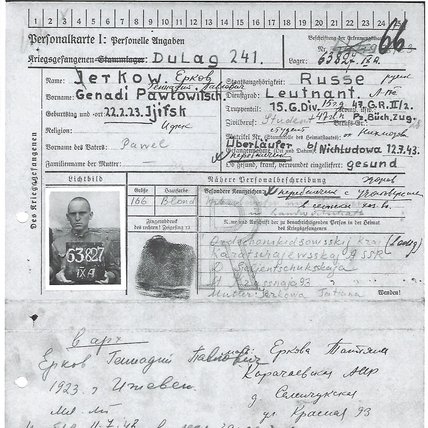

It was considerably harder for Ostarbeiter (Soviet forced labourers) and Polish forced labourers to flee. They were subject to constant surveillance not only at work but also in the camps and on the way to work. If they adhered to the racist regulations, such as wearing an identifying badge, they had few opportunities for flight. Many people, especially those from the Soviet Union, would also have had to pass through front lines and hostilities on their way home. In addition, their homes were often in already occupied territory. For people who were forced to work as prisoners of war or concentration camp prisoners, escape was even more difficult: POWs were housed by the Wehrmacht, and concentration camp prisoners were interned in heavily guarded camp complexes. Only very few people managed to flee concentration camps.

Resistance and self-assertion

Because of their great number alone, a coordinated resistance movement by forced labourers could have posed a real threat to the Nazis. A system of surveillance and harsh punishments was intended to prevent any form of resistance, and especially any conceivable cooperation between German resistance fighters and forced labourers. Nevertheless, there were isolated instances of organised resistance, mainly by Soviet prisoners of war and civilian forced labourers. The most important of these groups that we know of today was the Fraternal Cooperation of Prisoners of War. It was founded by Soviet POWs in Munich in 1943. Its members sought to make contact with civilian forced labourers and German communists. They aimed to organise foreign workers in Germany, organise acts of sabotage and overthrow the Nazi regime. After only a short time, the organisation had members in various cities in southern Germany. In 1944, the Secret State Police (Gestapo) uncovered the organisation and murdered many of its members in the Dachau concentration camp.

In 1944, when the German defeat was already imminent, more and more forced labourers tried to organise resistance groups. In Düsseldorf, for example, the Komitee Kampf dem Faschismus (Committee to Combat Fascism) was founded, whose members were mainly forced labourers from the Soviet Union and whose goals included acts of sabotage, contact with other forced labourers and the organisation of an uprising in the Ruhr region. However, realising this would have been very difficult. In most cases, the practical work of these groups consisted of mutual aid, for instance, in case of illness or to escape.

Forced labourers were taking a massive risk by forming a resistance group. If they were discovered, they would have usually been murdered by the Gestapo.

For this reason, many forced labourers sought other ways to resist or mitigate the coercion to work. Many people injured themselves on purpose to be assigned to less heavy work or to be able to take a break. Others deliberately worked slowly or produced defective goods to weaken the German military economy. Such acts were regarded by the Nazi regime as sabotage and punished as such.

Solidarity, communal singing, and mutual aid helped forced labourers arm themselves emotionally against day-to-day racism and cope better.

Further Reading:

Hans Coppi, Stefan Heinz. Der vergessene Widerstand der Arbeiter. Gewerkschafter, Kommunisten, Sozialdemokraten, Trotzkisten, Anarchisten und Zwangsarbeiter, Berlin 2012.

Ulrich Herbert, Von der "Arbeitsbummelei” zum "Bandenkampf”. Opposition und Widerstand der ausländischen Zwangsarbeiter in Deutschland 1939-1945. In: Klaus-Jürgen Müller, David N. Dilks (Hrsg.): Großbritannien und der deutsche Widerstand 1933-1944, Paderborn 1994, S. 245-260.