Punishment and violence

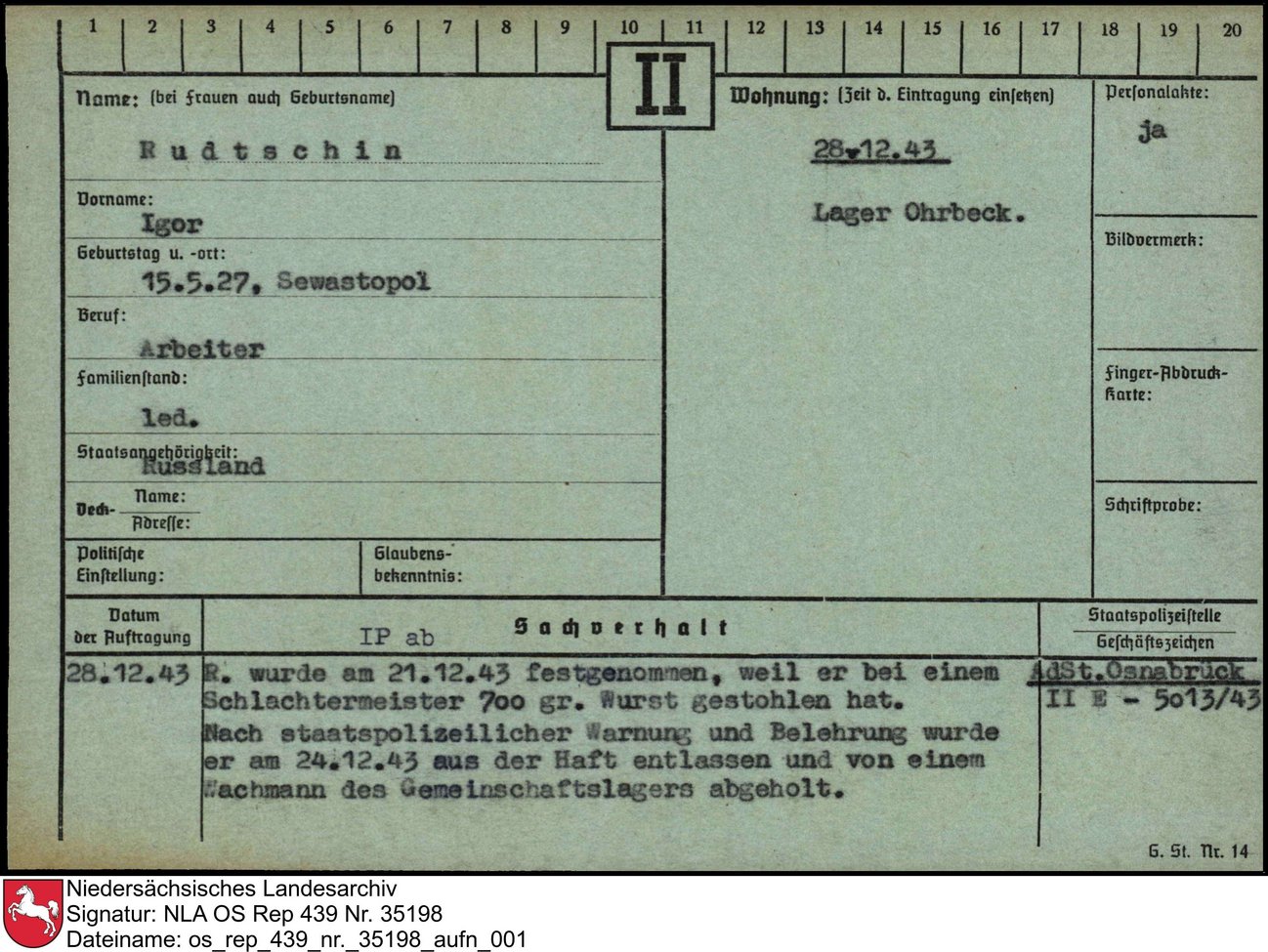

Civilian forced labourers in Germany and the occupied territories were surveilled, disciplined and punished in the Nazi state by the police, the SS, the Gestapo and the courts. As the German war economy depended on the labour of these people, the Gestapo took extremely harsh measures against any attempt to evade forced labour. Slow work, called “loafing”, was equated with sabotage, while arriving late or staying away from work, talking back and arguing were considered “breaches of the employment contract”. Harsh punishments were meted out for the slightest forms of resistance, as well as for private contact between Germans and forced labourers. Surveillance of forced labourers on a large scale was ensured by the many employees in the companies who were prepared to report any suspected violations to their superiors. It would have been very difficult for the companies to keep control of their forced labourers without the cooperation of their German employees. “Minor” infractions were punished by the company’s own supervisors, often with physical violence. Managers had a wide range of sanctions and punishments at their disposal, including deductions from wages or imprisonment in the company’s own cells. “Serious” cases, however, had to be reported to the Gestapo. Labour offices were also responsible for breaches of the employment contract and could decide on a case-by-case basis whether to involve the Gestapo.

The Gestapo’s powers

The Nazi regime gave the Gestapo powers far beyond those of any democratic police force. Not only could Gestapo officers investigate and arrest people, they could also impose and carry out their own punishments. One of their main instruments of terror was “protective custody”, which meant that they could imprison people indefinitely in concentration camps. Over the course of World War II, the Gestapo, the police and the SS gradually extended their powers to punish forced labourers. Their power culminated in what was known as “special treatment”, which meant the murder of East European prisoners. The decision to kill an interned person initially lay with the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) or the Reich Leader SS himself. As the war progressed, this power was gradually transferred to local Gestapo chiefs. From September 1942, the prosecution of men and women from Poland and the Soviet Union was left entirely to the police. The nature and extent of the punishment could be determined by the Gestapo and ranged from internment in prisons, work education camps and concentration camps to torture, physical abuse and the death penalty. Its actions were not subject to judicial review. In special cases, the Gestapo tried Polish and Soviet forced labourers, provided, of course, that the death penalty was a foregone conclusion.

Work education camps

The Gestapo developed its own system of camps, known as work education camps, to punish foreign forced labourers. These camps interned all those who had tried to escape or who had not done as much work as was demanded of them. The idea was to treat the internees in the work education camps so badly that they would do forced labour without any resistance after their internment. Some 280 of these camps were set up in Europe. They were an important means of forcing people to work for the German war economy. Around half a million men and women, mainly foreign forced labourers, passed through these camps. The work education camps were under the authority of the regional Gestapo offices, which made the decision to intern people without any judicial review. Internment in a work education camp usually lasted eight weeks, and on release the prisoners had to return to their old jobs or be assigned to a new one by the labour office. The forced labourers in the workplaces could see how badly the survivors of the work education camps had been treated, so the camps acted as a deterrent and had the effect of increasing the output of labour for the companies and the war economy as a whole.

The greatest danger for internees in a work education camp was the routine violence that prevailed there. From the beginning of their internment, they were subjected to humiliation and abuse. The camp staff arbitrarily punished the slightest infractions of camp rules with severe beatings or food deprivation. Camp leaders and guards imposed and carried out the punishments. The internees had no opportunity to defend themselves against accusations and punishments.

Special courts

The German courts were also involved in disciplining forced labourers. Many special courts were set up to hand down harsh sentences, often the death penalty, to mainly Western European forced labourers in fast-track trials. Of the 15,000 to 16,000 death sentences handed down by Nazi courts, some 5,000 were passed on mainly Western European and Czech forced labourers. Their sentences were made public and were intended to have a general deterrent and disciplinary effect.

Crimes committed in the final phase

In the spring of 1945, when it was clear to every German that the war had been lost, the level of violence perpetrated against persecuted groups, including forced labourers, escalated. Members of the Wehrmacht and the SS, as well as civilians, committed many massacres of concentration camp prisoners and forced labourers. On 20 March 1945, for example, Wehrmacht soldiers shot 71 Soviet forced labourers – 56 women, 14 men and one child – near Suttrop.

Further reading:

Gerhard Paul, Klaus-Michael Mallmann (Hg.): Die Gestapo im Zweiten Weltkrieg: "Heimatfront" und besetztes Europa (Darmstadt 2000)

Gedenkstätten Gestapokeller und Augustaschacht: Polizeigewalt und Zwangsarbeit: Die Gestapo Osnabrück und ihr Arbeitserziehungslager Ohrbeck (Osnabrück 2020)