Elisabeth Freund (1898-1982)

Elisabeth Freund was born in 1898 in Breslau (present-day Wrocław in Poland). After studying economics, she lived in Berlin. In 1922, she married her distant cousin, Rudolf Freund, with whom she had three children, Claire, Ursula and Rudolf. In her autobiographical book Als Zwangsarbeiterin 1941 in Berlin (As a Forced Labourer in Berlin in 1941), published in 1996, she describes that the Freund family came from “old-established Jewish families”. They regarded themselves as Jewish, but first and foremost as German and were not particularly religious. Elisabeth Freund earned her living by publishing self-help books on streamlining housework. Her husband was a lawyer and member of the board of directors of a large company in the iron industry.

From 1933 onwards, Jews in Germany were systematically deprived of their civil rights and property and forced out of public life. By making a normal life impossible for Jews in Germany, the Nazis wanted to force them to emigrate. In the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, they stipulated that descent alone would determine who was considered a Jew – whether or not they felt any connection to Judaism.

Separation of the family

Despite the restrictions, the Freund family initially stayed in Germany after 1933. As a lawyer trained in German law, Rudolf Freund found it difficult to find work abroad. They also assumed that Nazi rule would not last long. Elisabeth Freund described the years up to 1938 as “not always enjoyable, of course, but at least bearable”. It was only after the November pogroms of 9 November 1938 that the couple decided to emigrate as quickly as possible. This was not easy, however. Most countries only accepted limited number of Jewish refugees and it was almost impossible for Jews from Germany to get visas to enter these countries. The United Kingdom at least took in Jewish children. So, the Freunds, like many other German-Jewish parents, decided to send their three children there, where they would be able to stay in a boarding school or with a vicar’s family.

At the same time, Elisabeth and Rudolf Freund were trying to emigrate to the United States. As American immigration policy was very restrictive, in their desperation they also applied to other embassies, including the Cuban embassy. Elisabeth Freund describes the trips to the authorities and obtaining the right papers and certificates as extremely exhausting and humiliating.

As a forced labourer in Berlin factories

The Freunds’ lives deteriorated enormously during this time. They were forced to move into a small flat in Charlottenburg. In April 1941, Elisabeth Freund was called up for the Segregated Labour Service. From April to June 1941 she had to work on the hot mangle in an industrial laundry in Spindlersfeld.. Due to a previous illness, she suffered greatly from the hard work in the hot steam. But her complaints were ignored and in June 1941 she fell seriously ill. It was only when her health insurance confirmed that she could no longer work in the humid heat, that Elisabeth Freund was transferred to another company. From July 1941, she worked at the Erich & Graetz metal and electrical factory in Treptow, which manufactured mine detectors and detonators. Her job there was to sort small screws. In her book, she describes how hard and monotonous the forced labour was. She also lived in constant fear for her own future and that of her children, who lived far away.

Emigration at the last moment

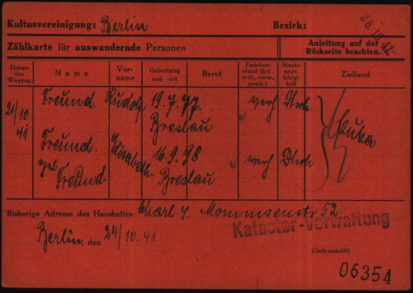

Events moved fast in 1941. The Freunds finally received an immigration permit for Cuba. At the same time, the situation for Jews in Germany was worsening; the emigration laws had been tightened and rumours of impending deportations spread. The Freunds obtained a special emigration permit via an old work colleague who had contacts at the Gestapo. Shortly before leaving for Paris, they learned that many Berlin Jews had been taken to an assembly point, the synagogue in Levetzowstrasse, to be deported to Poland. The Freunds were able to leave Germany on 19 October 1941, just before the Nazi regime imposed a total ban on emigration for Jews.

From Paris the couple travelled on to Lisbon, Portugal, where they had to stay for three weeks before finally taking passage on a Portuguese ship to Cuba. Bureaucratic hurdles meant that it was not until 1944 that they were able to emigrate to the USA.

In America, Elisabeth Freund worked as a photo-negative retoucher in Philadelphia, while her husband found work as an accountant. Their children were able to join them from Britain in 1946, and the family was finally reunited after eight long years. After her husband’s death at an advanced age in 1959, Elisabeth Freund embarked on a new career at the age of sixty-one, developing innovative learning concepts for blind children and opening a Touch and Learn Center at the Philadelphia School for the Blind. Her ideas were widely used in education for the blind. Elisabeth Freund died on 4 November 1982 in New York.