Administrative documents: work book and work book card for civilian forced labourers

Who created the documents and in what context?

In February 1935, the Nazi government passed a law introducing compulsory workbooks. Local labour offices were responsible for producing them. They gradually issued workbooks and workbook cards to every employed person in the German Reich. The workbook had to be kept at the workplace for the duration of employment, while the workbook cards were collected by the labour offices in a separate file. The information contained in these documents on the training and work experience of the employees made it possible to direct the workforce, especially into sectors relevant to rearmament plans and war production.

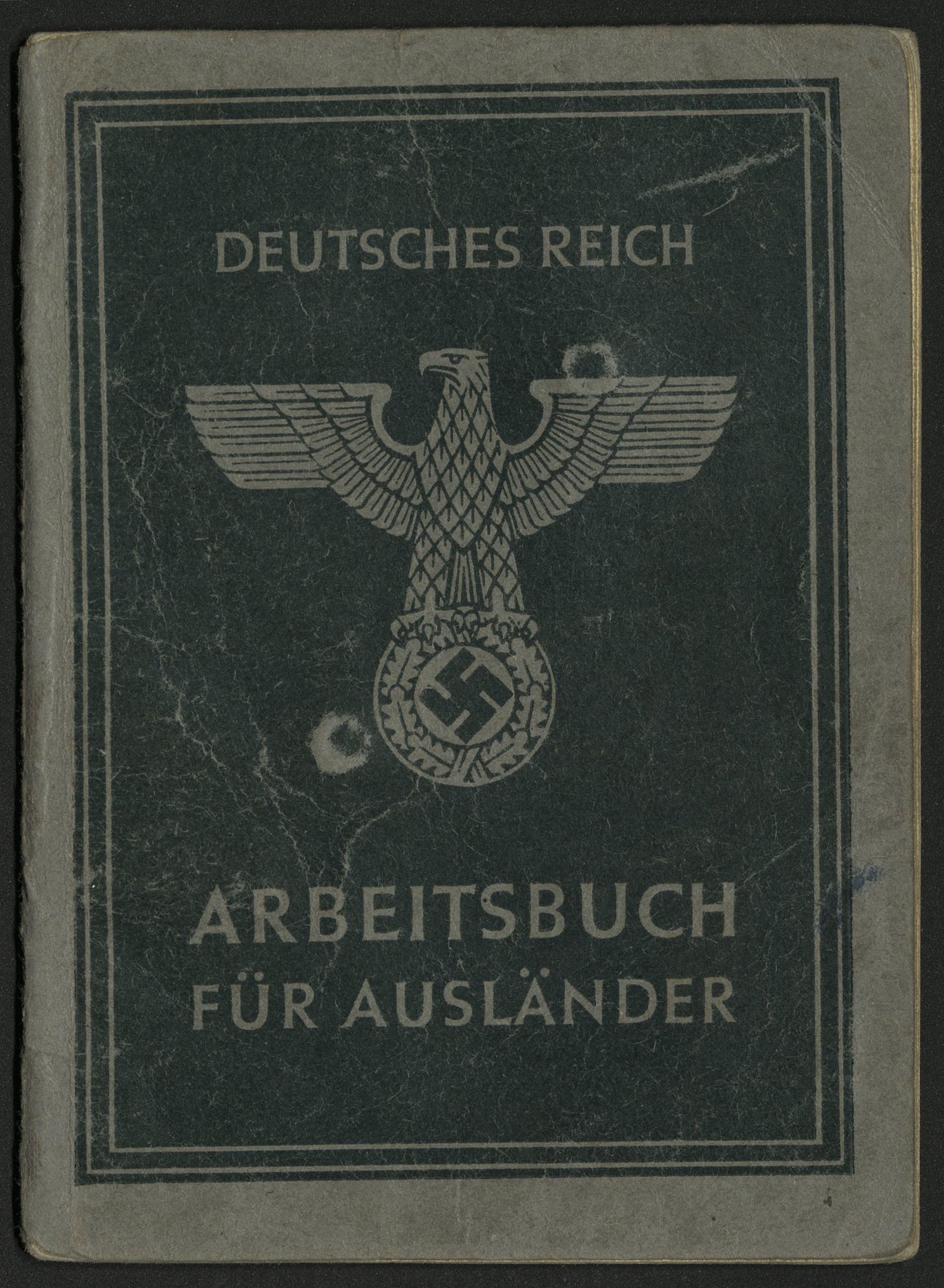

At first, civilian forced labourers were issued with the same documents as German workers. In May 1943, Fritz Sauckel, the Plenipotentiary General for the Deployment of Labour (GBA), introduced a “workbook for foreigners” and a separate workbook card for civilian forced labourers. At no time were forced labourers allowed to choose where they worked, but were assigned by the labour offices on arrival or selected directly by representatives of the factories.

What can we see?

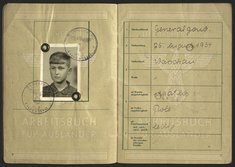

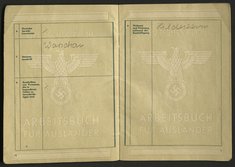

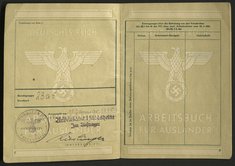

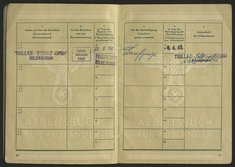

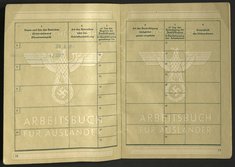

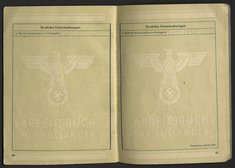

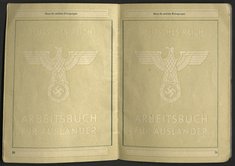

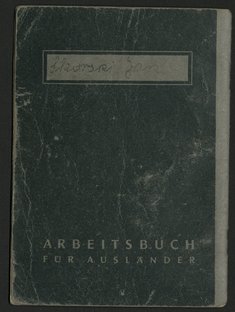

The first double page of the “workbook for foreigners” contains a foreword by the GBA, the person’s name and the workbook number. This number also appears on the workbook card and the work permit document. The following pages contain a registration photograph, usually taken at the forced labourer’s registration in the transit camps, and personal details such as education, work experience, other skills and current place of work. The issuing labour office is noted on page 8. Pages 10 to 25 are intended to record changes of workplace, which either rarely occurred or were not always recorded. The last two double pages are for recording medical examinations and findings, which were rarely recorded.

The double-sided workbook card summarises for the index file the main personal details, training, vocational skills and current employment.

What do these documents reveal about Nazi forced labour and what should be taken into account when dealing with administrative documents in educational work?

Nazi forced labour was bureaucratically organised and implemented as an interplay between state actors and workplaces. In addition to workbooks and workbook cards, labour offices, the police and other state agencies used documents such as work cards and work permits to control civilian forced labourers and to coordinate the deployment of labour in the German Reich. Companies and insurance companies also used a variety of documents to manage workers.

These documents contain personal details such as name, date of birth and place of work, and are therefore important documents in the search for a specific person who was forced to work. Today, they are often privately owned by former forced labourers. They were important pieces of evidence for people who needed to prove their forced labour when applying for compensation.

What do we not see?

These documents are not always completely filled in, so we have to expect gaps in the information that has been preserved. These documents do not tell us what the actual work was, or how many hours a day and days a week people had to work. Nor do they tell us what people experienced and felt during their time as forced labourers.

Links to further information

The eGuide of the Arolsen Archives presents numerous administrative documents for civilian forced labourers and offers extensive background information: https://eguide.arolsen-archives.org/

![[Translate to English:] Arbeitsbuch von Jan Skórski, ehem. Zwangsarbeiter bei Trillke, Dokumentationszentrum NS-Zwangsarbeit/Sammlung Berliner Geschichtswerkstatt, dzsw11015](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/d/csm_dzsw11015-Arbeitsbuch-Skorski-_3__afb99c70d8.jpg)